Gas–Surface Interactions in Hypersonic Reentry (Rarefied Regime)

At extreme altitudes—above 100 km and especially in low Earth orbit (~400 km)—Earth’s atmosphere becomes so rarefied that it can no longer be treated as a continuum. Instead, the behavior of gas transitions to what is known as free molecular flow. In this regime, individual gas molecules rarely collide with one another; instead, they interact almost exclusively with the surfaces they encounter, such as the heat shield of a re-entry capsule.

This environment, often referred to as the transition-to-vacuum or transitional regime, constitutes the first physical domain a spacecraft must navigate before entering denser atmospheric layers. Despite the near-vacuum conditions, relative velocities remain hypersonic—often exceeding Mach 25—which invalidates the assumption of isotropy found in static vacuum models. The result is not a spherically symmetric particle distribution, but rather a directed, beam-like flux of particles impinging on the spacecraft surface. It is the mechanics of this directed gas-surface interaction that we focus on in this paper.

In this regime, the spacecraft’s velocity dominates the thermal motion of atmospheric molecules. Although the background gas exhibits random thermal motion, the capsule’s velocity is so great that the surface perceives incoming particles as a unidirectional stream. Consequently, the gas can be modeled as a beam of independent particles bombarding a surface, with each interaction governed by statistical scattering laws.

Before introducing the surface interaction models, we must first define the key parameters that govern gas dynamics in rarefied regimes.

Mean Free Path and the Knudsen Number

One of the most critical parameters in rarefied gas dynamics is the mean free path $\lambda$, which defines the average distance a gas molecule travels before colliding with another molecule:

$$ \lambda = \frac{k_B T}{\sqrt{2} \pi d^2 p} $$Where:

- $k_B$ is Boltzmann’s constant

- $T$ is the gas temperature

- $d$ is the molecular diameter

- $p$ is the gas pressure

In the free molecular flow regime, $\lambda \gg L$, where $L$ is a characteristic length scale of the body (e.g., the capsule’s diameter). To quantify this behavior, we use the Knudsen number:

$$ \text{Kn} = \frac{\lambda}{L} $$When $\text{Kn} > 10$, the flow is considered free molecular, and continuum models such as the Navier-Stokes equations no longer apply. At this point, gas-surface interaction models become the primary tool for analysis.

In this context, the terms continuum flow, slip flow, transition flow, and free molecular flow are categorized based on the Knudsen number. Each regime dictates a different approach to modeling gas behavior near surfaces.

It is important to note that boundary layers form only in the continuum, slip, and transition flow regimes—not in free molecular flow. The distance from the spacecraft at which this boundary layer forms is determined by both the Mach number and the mean free path. Conceptually, it represents the distance a molecule travels after being emitted from the spacecraft surface (due to a collision) before it collides with an upstream molecule.

Free Molecular Flow and Thermal Accommodation

It is worth emphasizing that boundary layers—a hallmark of continuum and transitional flows—are no longer well-defined in the free molecular regime. In traditional fluid dynamics, boundary layers form due to viscous interactions near the surface, with their thickness depending on both the Mach number and the mean free path. However, at altitudes where re-entry begins (~120–400 km), the flow becomes so rarefied that molecular collisions are negligible compared to interactions with the spacecraft surface.

In such conditions, the so-called “boundary layer” can be loosely described as the distance a molecule travels after being reflected from the surface before colliding with another molecule. This is often approximated by:

$$ \frac{\delta}{L} \sim \frac{1}{\sqrt{Re}} $$where:

- $\delta$ is the characteristic boundary layer thickness

- $L$ is the characteristic length of the body

- $Re$ is the Reynolds number, which becomes poorly defined in the free molecular regime

Correspondingly, the Knudsen number $K$ becomes more relevant:

$$K \sim \frac{M}{\sqrt{Re}}$$As $K→∞$, we enter deep into the free molecular flow regime where the incoming flow is entirely undisturbed by the presence of the body. This leads to the fundamental assumption of free molecular theory: no shock waves or pressure disturbances form in the vicinity of the object. The rarefied gas moves ballistically, and the incident flow can be modeled as a stream of independent particles striking the surface directly.

Thermal Accommodation and Surface Energy Exchange

A key thermodynamic quantity in describing gas-surface interactions is the thermal accommodation coefficient, denoted $\alpha$. This coefficient quantifies the degree to which gas molecules thermally equilibrate with the surface upon impact. It is defined as:

$$ \alpha = \frac{dE_i - dE_r}{dE_i - dE_w} $$where:

- $dE_i$ is the energy flux of the incident molecules

- $dE_r$ is the energy flux of the reflected molecules

- $dE_w$ is the equilibrium energy corresponding to the wall temperature

Physically, $\alpha$ measures how much energy is transferred between the gas molecules and the surface during interaction. An accommodation coefficient of $\alpha = 0$ implies no energy exchange—the molecules reflect with the same energy they arrived with, analogous to a perfectly specular reflection. However, the momentum carried by the reflected molecule is still reversed, with a magnitude of $2mv$. Conversely, $\alpha = 1$ implies complete thermal accommodation—the molecules re-emit with an energy distribution corresponding to the wall temperature, resembling diffuse reflection in thermodynamic equilibrium.

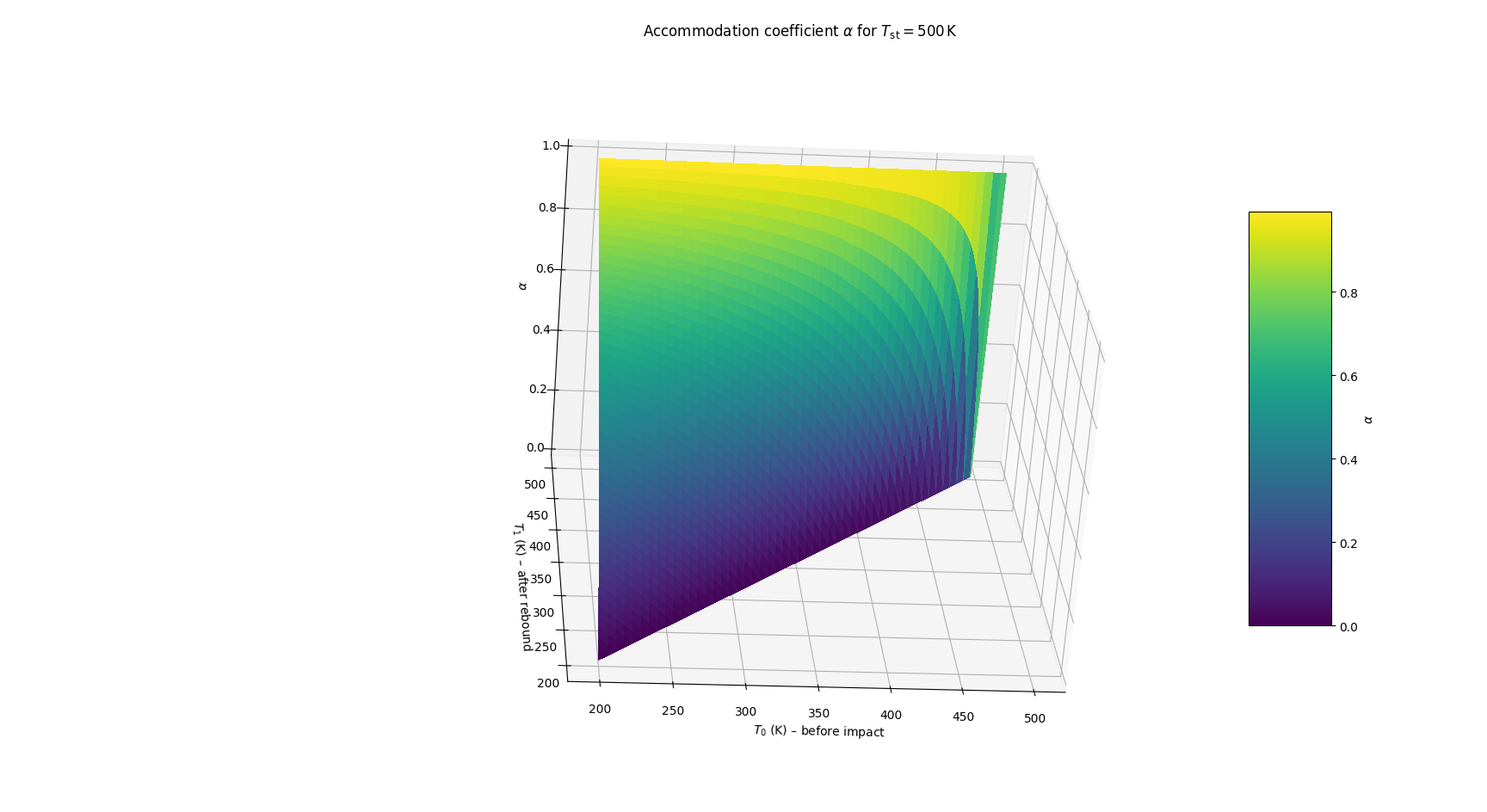

The figure above shows a representation of the accommodation coefficient as a function of the incident gas temperature, assuming a fixed wall temperature of 500 K. As seen in the plot, holding the wall temperature constant yields an approximately linear relationship between the accommodation coefficient and the incident temperature.

It is worth emphasizing that $\alpha$ represents the mean energy accommodation for the impinging particle. That is, the translational, rotational, and vibrational energy modes of the molecule are, in principle, each accommodated to the same extent. Experimental evidence suggests this is approximately true for translational and rotational energies, but vibrational energy is typically much less affected during surface collisions. If necessary, separate accommodation coefficients can be introduced for each energy component to develop a more accurate model.

Models

Maxwell Model

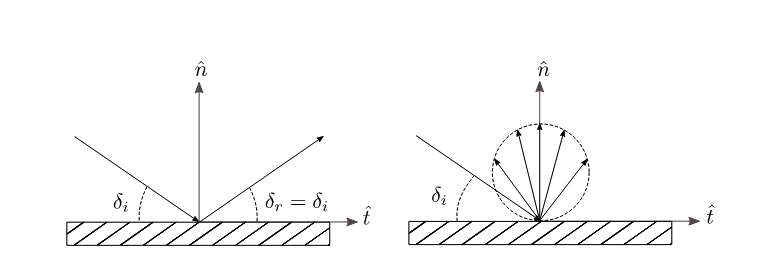

We begin our analysis with the foundational scattering model proposed by James Clerk Maxwell, which introduces a simplified framework for modeling molecular interactions with solid surfaces in the free molecular regime. Maxwell classified gas-surface interactions into two idealized types: specular reflection and diffuse reflection.

In the specular reflection model, gas molecules and the surface are treated as rigid, elastic spheres, and the surface is assumed to be perfectly smooth. Under these assumptions, each incident molecule reflects off the surface in a manner analogous to a light ray reflecting off a mirror: the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, and the magnitude of the velocity vector remains unchanged. Only the direction is reversed across the surface normal. This results in a purely deterministic interaction, preserving both kinetic energy and momentum parallel to the surface, and assuming no energy exchange with the surface.

$$ \Delta E = \frac{1}{2}m|v_i|^2 - \frac{1}{2}m|v_r|^2 = 0 $$No Change in Tangential Momentum:

Assuming the surface lies in the x–y plane, specular reflection preserves the tangential velocity components:

This can be visualized as:

This behavior is analogous to a billiard ball system, where—given the micro-geometry—one can predict the reflection angle based on deterministic geometry. This regime coincides with the case $\alpha = 0$, in which there is no thermal accommodation of the incoming particle’s energy.

In contrast, the diffuse reflection model describes a scenario where $\alpha = 1$. This implies that the reflected molecule re-emits with an energy distribution that matches the local surface temperature, completely losing all memory of its incident velocity and direction. Its outgoing state is governed purely by the thermodynamic state of the surface.

The direction of emission is governed statistically by the cosine law, which states that the probability of a molecule being reflected at an angle $\theta$ from the surface normal is proportional to the cosine of that angle:

$$ P(\theta) \propto \cos(\theta) $$This angular dependence reflects the fact that molecules are more likely to re-emit close to the surface normal than at grazing angles.

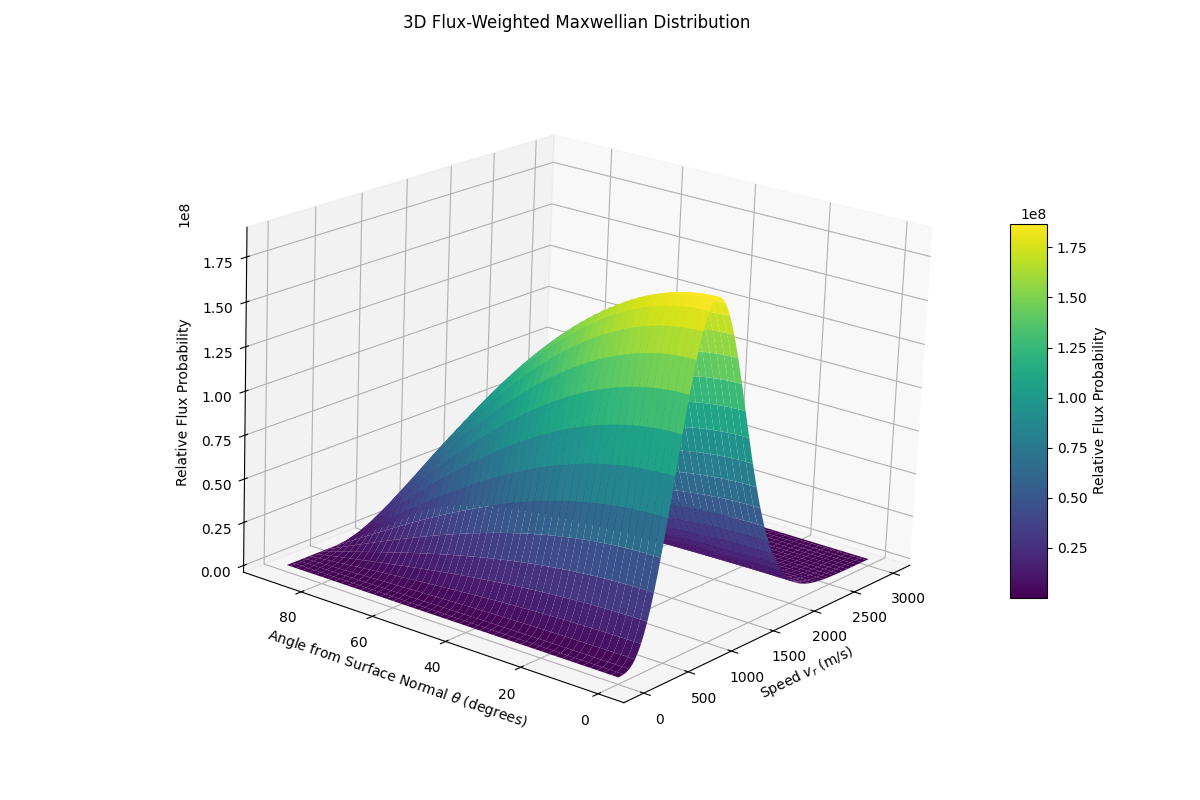

In addition to direction, the magnitude of the re-emitted velocity follows the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, weighted by flux considerations (i.e., the likelihood that a molecule leaves the surface with a given speed). The probability distribution for reflected speed is:

$$ P(v) \propto v_r^2 \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{m v_r^2}{2k_B T_w}\right) $$Combining the angular and speed dependencies, the full flux-weighted distribution of reflected particles in the diffuse regime becomes:

$$ f(v_r, \theta) \propto v_r \cdot \cos(\theta) \cdot v_r^2 \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{m v_r^2}{2k_B T_w}\right) $$![[3D flux weighted maxwell distribution.png|]]

In summary, we have two limiting models for molecular re-emission as a function of thermal accommodation $\alpha$:

- Specular reflection: deterministic, with $\alpha = 0$

- Diffuse reflection: fully stochastic, with $\alpha = 1$, following the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution and the cosine law for angular distribution

In Maxwell’s model, the behavior of the reflecting surface is described by a linear combination of the two classical scattering characteristics. That is, in accordance with the value of $\alpha$, a fraction of the incident particles undergo diffuse reflection, while the remaining fraction $(1 - \alpha)$ undergo specular reflection. The scattering kernel that describes this behavior is given by:

$$ K_M(\boldsymbol{\xi}_i \rightarrow \boldsymbol{\xi}_r) = (1 - \alpha)\delta(\boldsymbol{\xi}_i - \boldsymbol{\xi}_{r,\text{specular}}) + \alpha f_0(\boldsymbol{\xi}_r)|\xi_{r,n}| $$where:

- $\boldsymbol{\xi}_{r,\text{specular}} = \boldsymbol{\xi}_i - 2(\boldsymbol{\xi}_i \cdot \mathbf{n}) \mathbf{n}$ is the specular reflection velocity

- $\boldsymbol{\xi}_i$ is the incident velocity

- $f_0(\boldsymbol{\xi}r)|\xi{r,n}|$ represents the flux-weighted Maxwellian distribution

For molecules with moderate energy, this model captures the energy distribution reasonably well and served as a foundational model until the 1960s. However, its limitations become apparent when compared with experimental data.

One of the key limitations of Maxwell’s model is that it treats the accommodation coefficient $\alpha$ as a scalar that linearly interpolates between diffuse and specular reflection, without accounting for differences in energy exchange across translational, rotational, and vibrational modes. In orbital reentry conditions—especially for atomic and diatomic species like N, O, and O₂—these internal energy modes play a critical role in determining wall heating, momentum transfer, and boundary layer behavior.

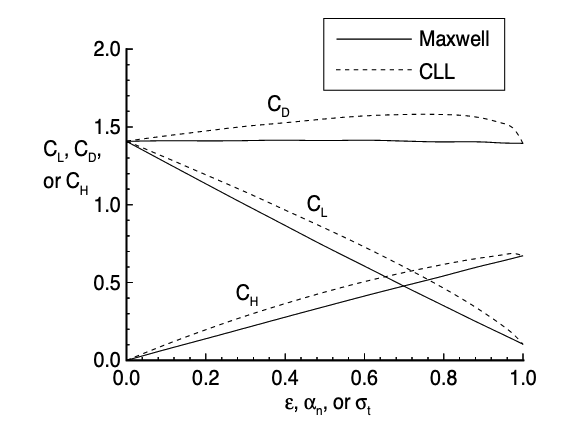

These deficiencies motivated the development of more comprehensive models, such as the Cercignani–Lampis–Lord (CLL) model. The CLL model enables independent treatment of normal and tangential momentum accommodation and introduces statistical correlations that better replicate observed experimental behavior.

Cercignani, Lampis, and Lord Model

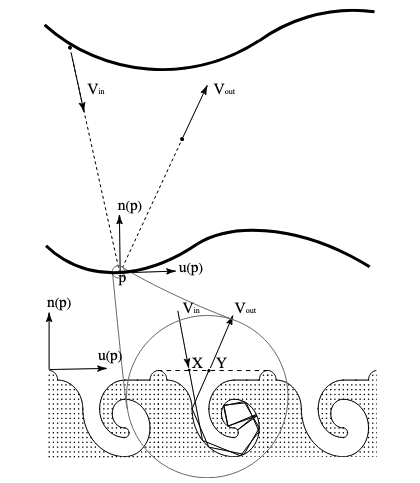

Molecular beam experiments have shown that scattering distributions often appear petal-shaped. In response to these findings, several models were developed to better match observed scattering behavior. A key limitation of the classical Maxwell model is its lack of specificity regarding momentum exchange—it primarily addresses energy exchange. To resolve this, two momentum accommodation coefficients were introduced to independently describe:

- Normal momentum exchange: $\sigma_n$

- Tangential momentum exchange: $\sigma_t$

These are defined as:

$$ \sigma_n = \frac{p_i - p_r}{p_i - p_w} $$Where:

- $p_i$: incoming normal momentum component (perpendicular to the wall)

- $p_r$: reflected normal momentum

- $p_w$: wall’s normal momentum (typically zero for a stationary wall)

Thus, $\sigma_n = 0$ implies perfect retention of incoming normal momentum—a perfectly elastic bounce.

Similarly, for tangential momentum:

$$ \sigma_t = \frac{\tau_i - \tau_r}{\tau_i}, \quad \text{where } \tau_w = 0 $$Where:

- $\tau_i$: incoming tangential momentum

- $\tau_r$: reflected tangential momentum

- $\tau_w$: wall’s tangential momentum (also zero for stationary walls)

So, $\sigma_t = 0$ means no change in tangential momentum—the gas “slides off” the wall without friction.

The Cercignani–Lampis–Lord (CLL) model assumes no coupling between normal and tangential momentum components. It treats the normal energy accommodation coefficient, $\alpha_n$, and the tangential momentum accommodation coefficient, $\sigma_t$, as independent tunable parameters.

The CLL scattering kernel is given by:

$$ K_{CL}(\vec{\xi}_i, \vec{\xi}_r) = \left[ \frac{\alpha_n \sigma_t (2 - \sigma_t)}{2\pi R_G T_w^2} \right]^{-1} \xi_{n,r} \exp\left( -\frac{\xi_{n,r}^2 + (1 - \alpha_n)\xi_{n,i}^2}{2\alpha_n R_G T_w} - \frac{ \left\|\vec{\xi}_{t,r} - (1 - \sigma_t)\vec{\xi}_{t,i}\right\|^2 }{ 2\sigma_t (2 - \sigma_t) R_G T_w } \right) \times I_0\left( \frac{ \sqrt{1 - \alpha_n} \; \xi_{n,r} \; \xi_{n,i} }{ \alpha_n R_G T_w } \right) $$\[ \qquad \bigl( \xi_{n,i} < 0,\; \xi_{n,r} > 0,\; 0 \le \sigma_t \le 2,\; 0 \le \alpha_n \le 1 \bigr) \]Breaking Down the Kernel

Tangential: Gaussian Distribution

The term:

$$ \frac{\left[\vec{\xi}_{t,r} - (1 - \sigma_t)\vec{\xi}_{t,i}\right]^2}{2\sigma_t (2 - \sigma_t) R_G T_w} $$is the kernel of a Gaussian distribution for the tangential velocity.

- Mean: $\mu = (1 - \sigma_t)\vec{\xi}_{t,i}$

- Variance: $s^2 = \sigma_t(2 - \sigma_t) R_G T_w$

Normal: Modified Maxwell–Boltzmann Distribution

The term:

$$ -\frac{\xi_{n,r}^2 + (1 - \alpha_n)\xi_{n,i}^2}{2\alpha_n R_G T_w} $$is a generalized kernel derived from the classical Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution:

$$ \exp\left(-\frac{mv^2}{2k_B T}\right) $$which now adapts to a correlated system between incoming and reflected normal velocities.

Normalization Factor

To ensure the kernel integrates to one:

$$ \text{Scaling Factor} = \left[\frac{\alpha_n \sigma_t (2 - \sigma_t)}{2\pi \left(R_G T_w^2\right)}\right]^{-1} $$Modified Bessel Function Term

$$ I_0\left(\frac{\sqrt{1 - \alpha_n} \, \xi_{n,r} \, \xi_{n,i}}{\alpha_n R_G T_w}\right) $$This term introduces a correlation between the incoming and reflected normal velocities:

- If $\alpha_n = 1$: reflection is fully thermalized — no correlation

- If $\alpha_n = 0$: reflection is perfectly specular — full correlation

- For $0 < \alpha_n < 1$: a smooth transition occurs between these extremes

This gives the kernel an elegant form:

$$ K_{CL}(\xi_i \rightarrow \xi_r) = \underbrace{\text{base Gaussian in } \xi_{n,r}}_{\text{Tangential momentum redistribution}} \times \underbrace{I_0\left(\frac{\sqrt{1 - \alpha_n} \, \xi_{n,r} \, \xi_{n,i}}{\alpha_n R_G T_w}\right)}_{\text{Coupling term for normal velocity correlation}} $$The CLL model offers a flexible and physically realistic framework for modeling gas-surface interactions in rarefied environments—such as hypersonic reentry, vacuum systems, and satellite drag modeling.

By introducing two independent accommodation parameters—$\alpha_n$ for normal energy exchange and $\sigma_t$ for tangential momentum exchange—the model captures anisotropic scattering behaviors observed in molecular beam experiments, including the petal-shaped angular distributions and partial retention of momentum.

Geometric Property of Ellipses

The need for high-fidelity models in rarefied gas dynamics becomes paramount in regimes where conventional continuum mechanics fails. As demonstrated, the Maxwell model provides a foundational understanding of gas–surface interactions by linearly interpolating between two idealized behaviors—specular and diffuse reflection—using a single energy accommodation coefficient, $\alpha$. While useful for basic analysis, this approach fails to capture the experimentally observed anisotropies in scattering, particularly in the presence of partially accommodating surfaces and complex surface microphysics.

The Cercignani–Lampis–Lord (CLL) model addresses these limitations by introducing a more refined framework in which the normal and tangential momentum components are decoupled and treated with separate accommodation parameters. This decoupling allows for independent control over both the directional memory and energy exchange characteristics of reflected particles. As a result, the CLL kernel is capable of reproducing the petal-shaped angular scattering patterns observed in molecular beam experiments, thereby achieving significantly closer agreement with empirical data.